Philippe Halsman, Dalì Atomicus, (1948)

Philippe Halsman, Dalì Atomicus, (1948)I connect more with Dalì in this photo than with the cats.

Yes, I'm an art historian. No, as yet there's not

The paper proposal itself--along with more happy jumping--after the break...

PROPOSAL:

For a genre as widely popular as mass-market paperback romance novels, there is much that lies unexplored and, therefore, unproblematized in scholarly discourse.[1] I propose to write about the role of masks/masking (and potentially masquerade) in [primarily] 20th and 21st century romance novels. Has masking as theme and plot device remained stable within the literature? How has it changed? Who is masked and why? What do they mask? What are the gender politics involved? How are masks and the act of masking structured in these writings? I anticipate that the story of Cinderella as an archetype will be a pivotal part of my inquiry; I may briefly explore masks and masking in fairy tales. The Regency era, being frequently depicted in such literature, will likely provide the bulk of primary source reading material.

For example, Julia Quinn’s novel, Romancing Mister Bridgerton, with its heroine who feels more "herself" at a masquerade—and who secretly writes a society column under a pen name—uses masks, masking, and masquerade as both explicit and implicit themes. Another example is that of Gaelen Foley’s Lord of Fire, in which a grotesque, carnivalesque masquerade is a scene of revulsion, arousal, and revelation; that this event occurs in the house of a spy, whose profession he conceals from everyone (except, in the end, his beloved), is only fitting. Eloisa James’s Duchess at Nightwill serve as [this proposal's] final example: the heroine spends a large portion of the book in drag as a male. Using these and other examples, I plan to explore different uses of and reactions to masks both literal and metaphorical, masking as an act of concealment, disguise, or liberation, and masquerade as setpiece and long-standing leitmotif.

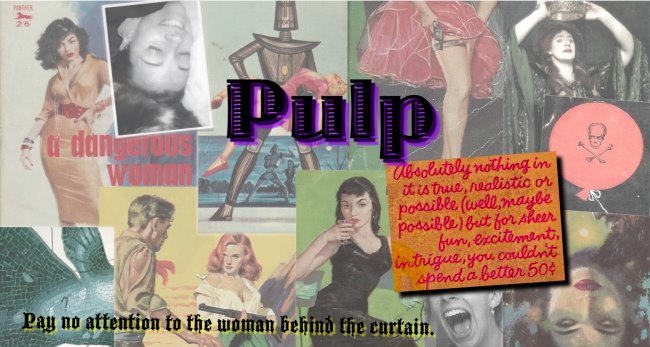

The proliferation of masking themes extends beyond the sphere of plot and even beyond that of the book itself. The covers of mass market paperbacks often consist of a titillating scene of seduction, peril, or high drama concealed behind the title on the cover. The act of purchasing and reading these books is often fodder for derision on the part of serious-minded folk—with concomitant shame on the part of the reader. In response, many readers of such works of fiction hide or deny reading them—indeed, they are often said to mask their enjoyment. A corollary is the double life that an author of such books sometimes chooses to lead: a high-profile example is that of Mary Bly, a Fordham professor who pens novels under the name Eloisa James.

I am also trying to feel out what sort of links there may be with Bakhtin's conception of carnival (if any)—both are escapist forms of popular entertainment underpinned and dependent upon levels of fantasy and inversion of "everyday life" (where the heroine always gets her hero, and the hero is always worth getting). (There are significant and enormous differences, of course; I am not going to claim that they are the same thing. ...On the other hand, carnival is only one type of expression of utopian fantasy—perhaps, as Nancy Scheper-Hughes suggests, a particularly male one[2]—while a more introverted activity (like reading) functions as both ideal for and idealized by a still-disenfranchised and often sexually exploited population.)

[1]They are read by millions—a glance at the New York Times bestseller list almost invariably shows a romance novel among the other escapist fare listed. Indeed, the Romance Writers of America data show that in the past five years the percentage of male readers of romances has shot up to 22 percent, "a shift that surely warrants someone's critical attention." Selinger, Eric Murphy. "Rereading the Romance," Contemporary Literature XLVIII, 2 (2007), p. 320.

[2] In Nancy Scheper-Hughes, "Carnaval," Death Without Weeping: the Violence of Everyday Life in Brazil (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), pp. 480-504, 555.

[2] In Nancy Scheper-Hughes, "Carnaval," Death Without Weeping: the Violence of Everyday Life in Brazil (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), pp. 480-504, 555.

And now, because I've just got to put this photo in, variants of Dalì Atomicus:

According to Wikipedia, repository of all known knowledge and supposition, it took 28 attempts before both Dali and Halsman were satisfied with the result.

7 comments:

i understood only about two words of this, but one thing i think i took away from it is that you're happy, so...congratulations.

Yes! Mission accomplished. (The mission of all grad students is to confound and confuse to convince others of one's genius.) Basically: I'm writing about masks in romance novels.

i know that rex p is going to win, but i didn't want to disappoint and tried my hand at a DF post. also, i'm in agreement with d.

I saw, tootsie pop. Really, all you needed to do was post of your deep and abiding friendship with me. A winner!! Just kidding.

Sort of.

what? our friendship's worth nothing?

If you haven't already done so, you might want to hook up with Smart Bitches, Trashy Books and Teach Me Tonight, where there's lots of pearls of wisdom about the romance oeuvre.

did a giant pile of art books fall on you and kill you?

Post a Comment